Entrepreneurship without a turnover increase and growth is unthinkable, but the usual instruments for implementation are useless and the right ones are missing!

A turnover increase and growth are as dogmatically linked to the business world as the New Testament is to Christianity.

Call-centre service providers, sales trainers, sales-process optimisers, marketing specialists, CRM providers, etc. Incredibly, there are so many providers on the market are geared towards helping companies achieve this goal.

“Why do you actually strive for a turnover increase or growth?”

When I occasionally ask my counterpart this question, I often catch them out because somehow this question doesn’t usually come up.

The real reason why they are pursuing a turnover increase as a goal is probably emotional. A reason that they as an entrepreneur rarely admit to themself. Examples:

- It feels really good for them if they can write on the website that they have branches in London, Shanghai, and New York.

- They will be perceived by others as successful and earn their respect.

The answer I get to my question, on the other hand, is usually intellectualised. My counterpart is looking for a logical-sounding justification, and in the end, usually says or paraphrases: “I am pursuing the goal because of positive economies of scale”.

Positive economies of scale

The bottom line is that a turnover increase and growth should ensure that the costs – broken down to one unit produced or sold – are always lower.

How could you check that this hypothesis is correct and that the bet is working? By an increasing profit/EBITDA margin of the company expressed as a percentage of turnover.

The first time I stumbled upon the fact that there must be something wrong with this theory was in my former business life where I had worked as a banker and an investment banker.

In many credit reports, there were talks of positive economies of scale, but I often could not see this effect in the figures of the client companies.

- Of course, my corporate clients have shown a higher margin here and there compared to the previous year, but just not as a recognisable multi-year positive trend matching the trend of continuous turnover increase!

- The company may have reported a higher euro amount year after year, but not a higher percentage margin.

You may object: “Yes, what’s the problem there? The main thing is that more euros go to the bottom line.”

This might be a naïve fallacy on your part, as growth requires prefinancing and the fluctuation of cash flows increase. This can lead to an increase in your probability of insolvency if the financing requirements are not met.

I will deal with this issue in Part 3.

And that leads to the second observation I have made again and again over the years:

An astonishing number of good, solid companies get into enormous difficulties, or even go bankrupt, precisely because they had previously started with a growth strategy.

Therefore, it is time for us to take a critical look at the idea of growth and look for possible explanations why a turnover increase and growth can set a negative spiral in motion.

Is the information from your managerial accounting useful?

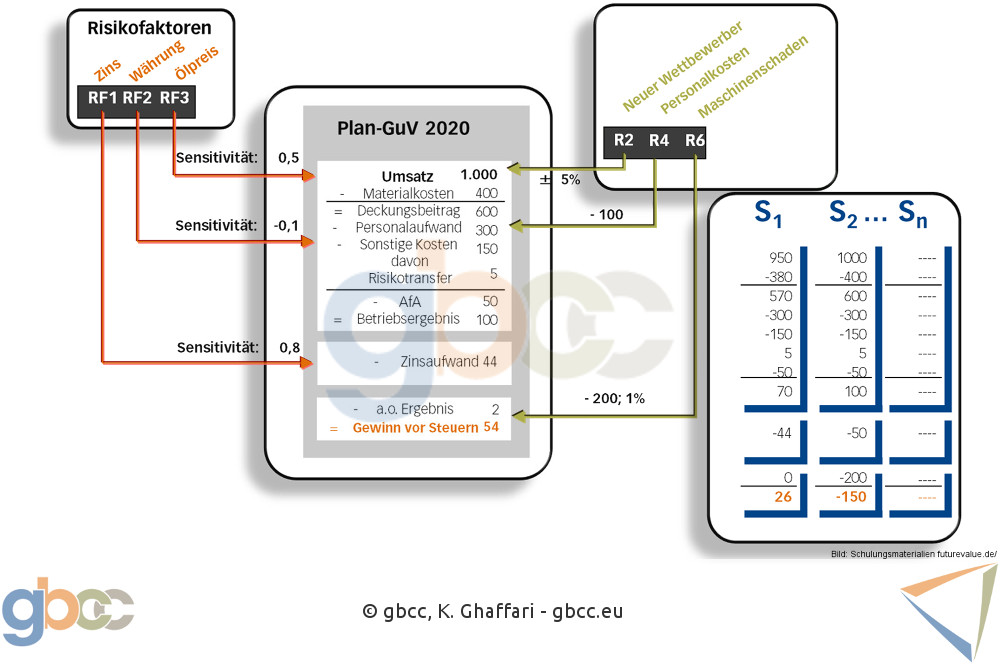

The decisive track leads us to the managerial accounting system that:

- Places the turnover at the top as the hub of the world and shows the costs in relation to this.

- Not only believes that you can squeeze the reality of your company into a period template but assumes that basic arithmetic is sufficient to represent the complex causality of your company.

If you are going to do period thinking, then you should also follow the path consistently:

Identify all significant variables and their interrelationships and, using a simulation technique, determine the possible range of outcomes and their probabilities of occurrence.

In fact, both the organisational structure in companies, i.e., the silo thinking in business areas and departments, and the periodically structured accounting system are amongst the real problems.

They prevent you from running your business in a profit-oriented way.

Unfortunately, the following applies: the usual controlling instruments, such as order or contribution margin costing, are at best irrelevant and misleading at worst.

To help you understand this bold thesis, let’s take the following order costing:

| Turnover | €1,000 | ||

| ( – ) | Material | €450 | (45%) |

| (=) | Gross margin | €550 | (55%) |

| ( – ) | Personnel | €300 | (30%) |

| ( – ) | Operating expenses | €50 | (5%) |

| (=) | Profit | €200 | (20%) |

Here I am primarily concerned with the €300 attributed to personnel expenses. This is a figure that is usually calculated as a percentage of turnover.

Is it advisable to treat personnel expenses as fixed costs?

Even if you are not always aware of it, personnel expenses are the result of a multiplication: number of hours x hourly rate.

Let us now assume that you determine and attribute an average hourly rate of €60 in this example. In this calculation, you assume that all employee activities (proportionally) related to this order amount to an average of 5 hours.

All activities include time

- In which your employee chases after you to finally get your sign off on a document or quote,

- You need to travel to the client to negotiate the order,

- That you spend in meetings to discuss the assignment with all parties involved,

- To carry out the order,

- To provide ongoing support to the customer,

- To write a bill,

- To collect the outstanding debts, etc.

Knowing the total process duration of an order and being able to express it in euros is the be-all and end-all of successful business management.

However, the percentage of entrepreneurs I have met over the years who can do this is negligible. Can you?

The human factor influences the required time span

An average of 5 hours already hints at the next difficulty because your company is a chain of individual activities between people who interact with each other.

The duration of many activities is usually not fixed, but a range. This range is significantly influenced by the human factor – especially by unclear and conflicting mutual role expectations.

Now, imagine a small company. Ms Smith there is a key person and carries out different activities that, in larger companies, would be divided amongst several people in different departments.

Role conflicts also occur with her, of course, but as she covers multiple roles, she can weigh up the pros and cons of taking specific actions before deciding on the best path to resolve the issue in no time at all.

Now, the small business is expanding massively, and Ms Smith’s work is being divided among several employees from now on. The questions are therefore:

- What happens if staff and management do not take the time to set up internal processes, discuss ways of working, and identify and resolve role conflicts?

- How will the company develop? Will it be a smooth or chaotic process?

- What impact will this have on the company’s future productivity and profitability?

Conclusion:

Treating personnel expenses as fixed costs and using them as a proportion of turnover to calculate orders is at best irrelevant and misleading at worst.

This is because your business is a chain of individual activities between people who interact with each other. The duration of many of these activities is usually not fixed, but a range. This bandwidth is significantly influenced by the human factor.

Knowing the possible range of internal processes and being able to express it in euros through calculative hourly rates is the be-all and end-all of successful company management and the basis of a successful growth strategy.

But that’s not all. Customer behaviour also has a significant influence on the duration of the activities. This is what we will look at in the second part. We will look at what the “wrong” customers are all about, and what happens when we advertise with a hyper focus on sales.

And after we have sufficiently appreciated human resources, we will turn to the topic of financial resources in the third part; specifically, debt financing and equity financing.