Being constructive and solution-oriented is “in”. People who point out problems really have a hard time. In this article, I would like to take a stand for them by taking a diversion and looking at “critical rationalism” and the “Munchausen trilemma”.

At the beginning of my working life, I experienced supervisors who said things like: “If my employees want attention, they should get a dog”.

Praise, recognition , or appreciation? Not a chance! The Swabian proverb “not scolded is praise enough” describes this mentality quite well.

That was the spirit of the times. A real boss was a leader and told us clearly where to go. Employees only had to follow. Constructive and solution-oriented thinking was not necessary – and usually not really desired.

Being constructive and solution-oriented is “in”

Now, we are in different times. Employee motivation is the order of the day because you want committed employees. That praise, recognition and appreciation are part of it is, therefore, beyond question. The task is rather: How do you motivate others properly?

And the common denominator of all possible answers on “how” apparently boils down to this:

- You are positive and benevolent towards others.

- You respond to the needs of the other person, ensure they are heard and include them, so they are invested in the journey.

- If you cannot avoid having to point out mistakes, you must at least make an alternative suggestion in a constructive and solution-oriented manner.

And as such a superior, you naturally also want such employees. Consequently, job advertisements must explicitly indicate that constructive and solution-oriented employees are wanted.

This is the mentality that is “in” these days. And we encounter this phenomenon in the most diverse guises and packaging. For example, service providers who work with your employees distinguish between “initiators”, “followers” and “stoppers”; alternatively: “real customers”, “visitors” and “complainers”.

Problem-oriented stoppers and complainers are not constructive and solution-oriented

The stoppers and complainers are, so to speak, the mucky pups from the neighbourhood who no one wants to play with.

What about praise, recognition, or appreciation for this group of people? Not a chance!

This is because their mentality does not correspond to the zeitgeist and is not perceived as constructive, solution-oriented, and valuable. Furthermore, they are implicitly or even explicitly assumed to have a negative intention behind their appearance: they are destructive, and their aim is to stop progress.

Furthermore, being made aware of problems and obstacles does not appear to be a valuable service for anyone – unless, of course, the person directly provides an alternative solution in a constructive and solution-oriented manner.

And if the person doesn’t know any better and is also linguistically perceived as “violent” and encroaching, then even the last drop of goodwill is gone. This person should urgently be removed from your community. Otherwise, there is a great danger that they will infect others with their negativity, isn’t that so?

In this article, I would not only like to take a stand for this group of people, but even go so far as to claim:

Engaging with these people and dealing with them is probably the best thing that can happen to you! And they very much deserve your praise, recognition, and appreciation.

To make it easier for you to understand this unorthodox conclusion, we must first take a diversion by addressing the question:

What is considered a “truth” in a community?

Where do you find it? How do you find it? How do you recognise it?

Since the dawn of civilisation, such questions have occupied the brightest minds. Philosophers, sociologists, etc.; they provide so many exciting (and highly contradictory) answers.

Can I offer you my own answer? No! Because my career path had nothing to do with these disciplines and their questions. Fortunately, nothing has ever stopped me from dealing with issues that are “beyond my pay grade”.

However, my motivation is never academic, but always purely practical: if a topic seems relevant to me for the success of my work as an “Interim Co-CEO“, then I deal with it. It’s that simple.

And this topic is highly relevant to the success of my work. You will soon see how, so I ask for a little more patience.

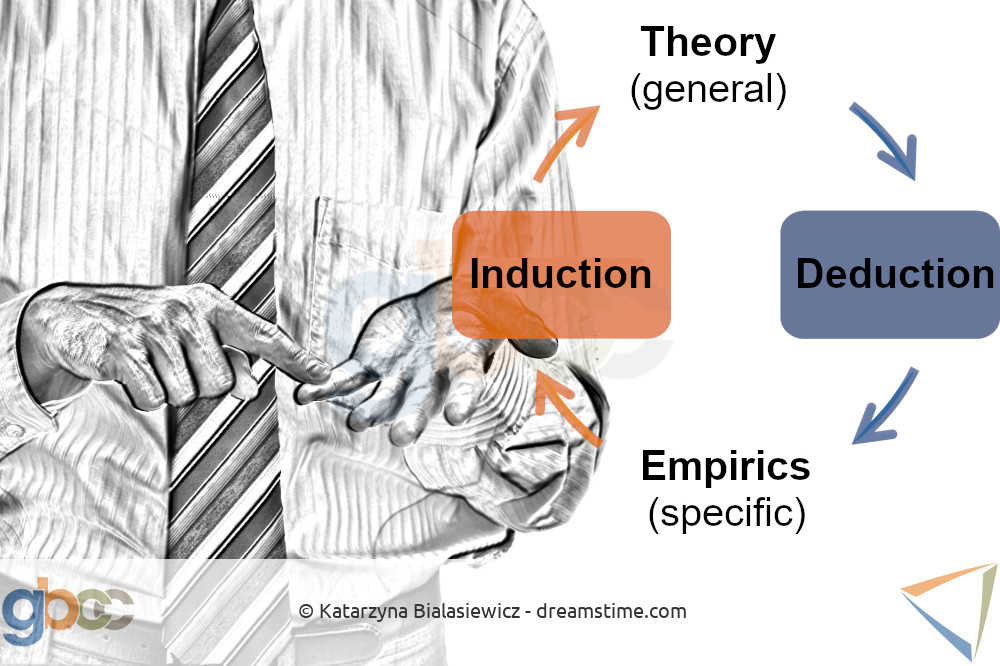

Deductive reasoning: from the general to the specific

What is the point of all this truth seeking? Answer: because you feel safe when you have certainty!

If you find a (generally valid) truth, you can make a true – and therefore safe – statement about a concrete case and derive actionable options.

This is the process of deductive reasoning. Example:

“All human beings are mortal. I am a human being, so my death is inevitable. So, I will write my will in time.”

Mathematical theorems (Pythagorean theorem) are formed deductively, but political ideologies and religions also function deductively. They are based on a dogmatic proclamation of an absolute truth:

- “Marxism/capitalism is so-and-so and therefore applies…”.

- “God exists and created everything. Full stop.”

Inductive reasoning: from the specific to the general

What about the other way around? How do you find – starting from what can be observed around you – the underlying truth? So how do you get from “I see people dying” to the universal truth “all humans are mortal”?

Welcome to the world of scientific thinking.

Interestingly, the common entry point begins with a dogmatic premise: there is a discoverable universal truth. However, this is “veiled”. You therefore “only” need to find and lift this veil.

You therefore ask yourself: “After I have successfully lifted the veil, what will I find?” With this hypothesis in mind, you set out to find a way to successfully lift the veil.

1st possibility: you actually find what you thought you would find. Then you shout aloud: heureka! The (rhetorical) question in this context is: have you really discovered the truth beyond any doubts?

Or have you merely overlooked, or even blanked out, the circumstantial evidence that would disprove the hypothesis?

Let’s take Newton’s law of gravity. It was recognised as a “truth” as one of the four basic forces of physics. You could/can work with it practically, for example, to build lifts. But in larger cosmic dimensions, there was a target-actual deviation in calculations.

It was only a few centuries later that Einstein’s “General Theory of Relativity” replaced it. The above-mentioned deviation disappeared, and new practical applications were made possible, such as satellite navigation.

Is that the truth? No! Because we are dealing with an as yet unexplained target-actual deviation on the quantum-physical level. This is the transition to the:

2nd possibility: a significant target-actual deviation which cannot be explained away. What then? Well, that depends:

2a) If you believe that your initial hypothesis is still true, then you have probably not yet discovered and lifted the “right” veil. So, you keep on searching.

2b) If you have reason to believe that the veil has been lifted and you have just seen the truth, then your hypothesis was probably wrong or incomplete. You must form a new hypothesis that describes your actual observation. “String theory” and co. sends their regards. And then you continue with the verification of the new hypothesis.

Caution: if you proceed as described above, then you are intrinsically constructive and solution-oriented! That is, not only when you positively and cheerfully form hypotheses and establish a review process, …

… but also, when you frustratedly take the target-actual deviations seriously and, if necessary, have to discard (with a heavy heart) the hypotheses that you have laboriously worked over.

But the zeitgeist sees it differently, because it seems to apply the idea that anyone who does not join in shouting “eureka!” is not constructive and solution oriented.

Can you find irrefutable truths?

The theory that you can find an absolute truth by means of an inductive process is flawed – to put it mildly.

- The pursuit of getting certainty and feeling secure and

- The pursuit of finding the truth seem to be factually mutually exclusive.

In other words: 1. probably ensures that you lose sight of 2. sooner or later.

Hans Albert, German sociologist and philosopher, sums up this insight as follows:

“All certainties in cognition are self-fabricated and thus worthless for grasping reality”.

Treatise on Critical Reason

The Munchausen trilemma

Why is it not possible to find and (scientifically) prove a fundamental and irrefutable truth? The short answer is because every attempt at proof leads to one of three possible outcomes, which Hans Albert calls the “Munchausen trilemma“:

- Outcome 1: to an infinite regress.

- Outcome 2: to a circular argument.

- Outcome 3: to a termination of the evidentiary process by “immunisation” against objections.

The 1st outcome is what happens if you actually wanted to make an effort to justify a statement as being true beyond a doubt. For every hypothesis you put forward to justify it, it inevitably demands a new justification. Ad infinitum.

- If you have ever experienced a child who responded to each of your answers with “why?”, then you know exactly what we are talking about here.

A conceivable way out of outcome 1 is through outcome 2: you start to turn in circles argumentatively to prevent having to find new arguments.

- For example, A says: “God exists.”

- B then asks, “What makes you think that?”

- A: “Because it’s in the Bible.”

- B: “And why should the Bible be true?”

- A: “Because it is the word of God.”

If this doesn’t work either, and the other person doesn’t give up, then you only have the 3rd outcome as a way out: you eloquently glorify a thesis as a “truth” and “immunise” yourself against further objections.

This is the equivalent of “Enough!” but just decorated with academic tinsel.

Munchhausen trilemma in everyday life

Having said that, immunising oneself against the arguments of others is probably also part of the zeitgeist. Unfortunately, I see this every day on social media:

Person A posts a half-baked thesis as the ultimate wisdom. You take the time to refute the thesis.

What does A do? They write: “I don’t see it that way” and seriously believe that everything necessary to counter your statement has been said.

How could it be otherwise, when our “role models” behave in exactly the same way? When I observe scientists and other bright minds of our time in discussions, I frequently have a strong déjà vu of a religious-dogmatic debate:

For I am not observing two people who are genuinely interested in lifting the veil together, I am instead observing the struggle of two people for the exclusive claim to a position of power:

- “I am the person who wants to proclaim an authoritative and true interpretation of reality and convey certainty and security. Therefore, dear colleague, don’t give me logic, because I am immune to all the arguments you present.”

“Truths” in everyday business life

And this phenomenon affects not only the natural sciences, but of course, also economics. For me, it is therefore not surprising that I find dogmatic “truths” in companies that are taken for granted without being critically questioned.

Some of them are dependent on the zeitgeist:

- Employees must be led with a firm hand.

⇒ Employees must be motivated. - Good employees obediently follow instructions.

⇒ Good employees think constructively and in a solution-oriented manner. - We need to describe our products in superlatives.

⇒ We need to address our customers emotionally and respond to their needs. - We must restrict our (human) resources to be perceived as cheap and affordable as possible.

⇒ We must appear in a way that we are perceived as “woke” and environmentally conscious.

Others are evergreens and are considered to be without any alternative:

- Businesses need to grow and expand.

- Companies need a hierarchical structure.

- Companies need leaders.

Critical rationalism: “constructive” and “solution-oriented” redefined

Critical Rationalism (CR) was founded by Karl Popper († 1994) and is not simply a theory but is an attitude to life in itself. One that admits – and relies on – that one can and will err.

If I have understood it correctly, CR does not rule out the possibility that a universally valid truth can actually exist. A question that seems completely irrelevant to me personally: I don’t know, and I don’t care. Because I agree with CR’s Conclusion and that is the only thing that is relevant to me:

We humans are limited in our abilities to fully grasp the actual reality around us. Thus, we can never really know whether our experiences and opinions correspond to actual reality or not.

Consequently, any theory – scientific, religious, or esoteric – is fundamentally unprovable. Consequently, it is most likely a waste of time, money, and effort to try to prove theories.

What does that leave you with? A lot!

You can namely try to find out if and where your theories might be flawed and how you could eliminate discovered flaws. If you proceed in this way, you will not only be truly constructive and solution-oriented, …

… but you will furthermore ensure that you are spared the “Munchausen trilemma”!

CR in practical work with companies

To illustrate this, let’s take the statement “companies must grow and expand”, which (almost) all market participants accept as absolutely true. Do you too also accept it as the absolute truth? Many observable services in the market are logically built on this: Sales staff are trained, or marketing campaigns are designed, and KPIs are defined to “prove” that one has chosen the right path.

Is it true that your company, which uses my advice, needs to grow? I don’t know that! I am not interested in that! What do I care about instead? I rather ask you this question instead, as your answer gives me the proper benchmark for doing my job: let’s assume that your thesis is true, and you manage to grow. What exactly do you think it will do? You may answer:

- “The achievable cost savings due to economies of scale will increase our ‘EBITDA‘ margin”.

Well, that sounds much better! I can work with that because:

A useful thesis already contains the hint on how you could recognise a faulty or insufficient theory. (Cf. „falsification“ according to Karl Popper.)

But I can also ask further: is it possible that your EBITDA margin can increase, but the increase is sometimes more and sometimes less? What is your theory that explains this range?

Now, let’s say that while analysing your company, we stumble upon the fact that your EBITDA margin is declining despite growth. What will happen then?

When is being constructive and solution-oriented possibly destructive?

Without a CR mindset, there’s a huge danger of immunising yourself against facts because you do not want to discard the supposed truth. You will then continue in the same direction unperturbed. To justify this, you will say sentences like “exceptions confirm the rule”.

No, they don’t. With such an attitude, you do not achieve real progress. Quite the opposite, in fact. A considerable number of companies get into difficulties or even go bankrupt precisely because they had previously grown in an uncontrolled way.

Your supposedly constructive and solution-oriented attitude then has a destructive effect on your company.

You develop your company in a stable way if you strive for a theory that eliminates the exceptions.

And that is what I ultimately do: I help you find out how the results are delivered in your company and what those responsible in your company can do to optimise it.

And in the context of this review, it is very possible that you will (temporarily) say goodbye to the idea of growth because of this.

Theory review in a complex-causal environment

When checking the thesis, you will inevitably realise that your company functions “complex-causally“!

By this I mean that many actions cause various effects, reactions, and interactions. And since people are involved, this machinery has an “inner life” that you cannot explain and control according to the causality of cause and effect. You must additionally consult the findings of “systemic causality” to move forward.

When it comes to identifying relevant variables, you are confronted with your own blind spot. When I come in, there is one more person with an outside view to reduce the likelihood of something being overlooked.

But why settle for just a few people when there are over tens or hundreds of employees that could also be thinking along with you?

And that is exactly the reason why I would prefer to involve all your company’s employees within the framework of my “E. A. G. L. E. approach“. Those who see the glass as half full are just as welcome to me as those who perceive it as half empty.

Stoppers and complainers are very much constructive and solution oriented – only differently

And even those who don’t have their attention on the water level at all, but instead want to get upset that the glass is dirty or has a crack, are just as welcome to me! Because:

You can only assess the relevance of an observation for yourself when you become aware of it!

And here we’ve come full circle and we are back to the supposed “stoppers” and “complainers” who are allegedly not constructive and solution oriented. They are often the key to identifying errors inherent in the system and to developing good hypotheses for solutions.

Facts versus intuition or gut feeling

Speaking of the solution hypothesis, one question remains to be conclusively clarified, which I would like to demonstrate as follows:

Let’s assume that your employees develop a solution which we’ll call hypothesis “A”. To validate the thesis, all relevant (risk) factors are systematically recorded, and possible scenarios are stochastically modelled.

The result of this work underlines the (probable) accuracy of hypothesis “A”.

But you have the solution which we’ll call hypothesis “B” in mind, which is not supported by hard facts. However, you reply: “Not only does my gut feeling say that path B is correct, but also my right earlobe twitches. I know from experience that when that happens, I can be quite sure.”

Now what?

Well, in my opinion, this is not all that different from the thesis above regarding turnover growth. Again, I can hardly know whether your thesis will turn out to be true for your company or not. Therefore, I would draw your attention to the consequences of a possible mistake and therefore recommend the following:

In view of the liability risks arising from the introduction of the “Corporate Stabilisation and Restructuring Act” on 1st Jan. 2021, it is advisable not to put everything at stake, but to instead set up a creative experimental corner.

Conclusion:

- When others point out a (logical) error to you, you can hope or wish that they have your best interests in mind.

- You can hope or wish that they will communicate with you in a non-violent and non-hostile way.

- And you can even hope or wish that they will not only draw your attention to the error, but furthermore offer you an alternative proposal.

However, in my opinion, all this is nice to have – desired, but not necessary, because making you aware of a possible mistake is already the greatest service someone can render you.

- If you perceive a benevolent attitude on the part of the person, but do not consider the hint to be relevant, then their initiative is worthy of recognition in its own right.

- If the tip turns out to be potentially useful, then the person definitely deserves to be praised by you and encouraged in their behaviour.

- Who knows, maybe one day you will be surprised to discover that you have learned to appreciate people whom you used to perceive as “stoppers” and “complainers”.

And who knows, perhaps you will subsequently experience that these people will feel increasingly motivated to fulfil your aforementioned wishes in the future.